This was a small side note when I did my article on writing Jewish characters (now available on YouTube!), and all I mentioned was that it’s a Jewish taboo to name a baby after a living family member, but I feel like I missed an opportunity. So, I want to expand on the subject of naming Jewish characters!

I’ve always loved names and naming characters, so this is a topic near to my heart. Names are amazingly fun. They can tell you about a character’s personality, their history, their culture, and their future. Naming is one of a writer’s greatest tools and the very first thing any reader sees about a character. It needs to be done well.

When naming a Jewish character, there’s a lot to consider. There’s meaning, history, legend, language, ethnicity, and time period to take into account.

Hebrew Names

A Hebrew name is used in the Jewish community primarily for purposes of ritual and religion in the diaspora. Some see it as a “real”, if secret, name, with a secular name being a sort of mask society demands, others see it as an additional name, or even a useless name.

An example of when a Hebrew name would be used would be praying for a person’s health if they’re sick or calling a person to the bimah (altar) to read from the Torah in synagogue, such as for a Bar or Bat Mitzvah service or other occasions. A Hebrew first name can be the same as an English name, or it can be very different. Jeffrey might become Arieh and Ashley might be Simcha, but Sarah remains Sarah. Other names like Joseph or Rachel are anglicized versions of Hebrew names and so might become Yosef and Ra/ch/el (with the ch in Rachel being pronounced the same as the ch in Chanuka).

The practice of having separate Hebrew and secular names is not a new one, especially in locations where Jews were an endangered minority. For an ancient example, you can look at the story of Esther. Esther was not originally a Jewish name, but a Persian one. Esther’s Hebrew name was Hadassah, which means myrtle. In the story, she uses the Persian name Esther to hide her Jewish identity to stay safe.

When choosing a Hebrew name for fictional character, be sure to take into account the meaning of the name. For example, Arieh means lion and Simcha means happiness. Many popular Hebrew names that are also words with meanings, usually nature words, are unisex, like Aviv [spring], Tal [dew], and Or [light]. That said, Hebrew is a very gendered language (the word for table is masculine, the word for shirt is feminine, etc.), so names ending in -ah or -t are usually feminine names, such as Liora or Ronit.

Names with biblical origins are usually not unisex. If you want a name connected to a story in the Torah, be sure to know what the story is, as it can indicate foreshadowing. For example, a character with the Hebrew name Shimshon [Samson, in English] might be destined for tragedy, romantic betrayal, and/or death, especially if he cuts his hair at any point in the narrative. A character named Gideon might be destined to overthrow and kill a king. A character named Rut [Ruth, in English] might be destined for a Cinderella type rags-to-riches romance.

Hebrew names are given by parents to their children as babies or sometimes by a Hebrew teacher assigning a name in a language class if someone doesn’t have one yet. Converts are given the opportunity to choose their Hebrew names. My father, for example, chose the Hebrew name Shlomo, because he wanted to be wise like King Solomon, and Shlomo is the Hebrew version of Solomon.

There is one notable occasion in which someone’s Hebrew name will be changed. Many Jews believe that names hold power. So, if someone receives a diagnosis for something life threatening or they become extremely ill, they might have their Hebrew name changed to either Chaim for a boy or Chava for a girl, as both these names mean “life”. The hope, in this case, is that the name will empower them to survive and live a full life.

A Hebrew last name is simple to do – its simply ben (son) or bat (daughter) Father’s Hebrew name. A less commonly used option sometimes found in Reform or Reconstructionist Jewish communities is the non-gendered mi’beit or mibeit, which means from the house of. So, if my first name is Tzipora, that makes me Tzipora bat Shlomo. In modern times, many less orthodox congregations and traditions will also include the mother’s last name. If my mother’s last name is Or, that would make me Tzipora bat Shlomo ve Or. Tzipora, daughter of Shlomo and Or.

This can be used to add another layer of meaning to your fictional character. Combining the literal meaning and biblical stories, Tzipora bat Shlomo ve Or translates to Bird/Wife of a Prophet, daughter of Wise King/Peaceful person and Light. That’s a lot of meaning and foreshadowing packed in a name like that. The bird part may indicate a desire to be free and fly or it may indicate a singer. Tzipora is also the name of Moses’s wife in the Torah, so there’s a connection to a story to be aware of when using that name. Being the daughter of a wise man or leader whose name means peaceful and the daughter of light indicates an intelligent character with a strong moral compass and capacity for compassion.

Please note if your character is a convert, then their Hebrew last name will be ben/ bat/mi’beit Abraham ve Sarah. This is also used when someone’s parents are unknown, a reference to the belief that all Jews are descendants of the biblical figures of Abraham and Sarah. While this is meant literally for those born into it, its considered more of an adoption into the family for converts rather than a biological connection.

When picking a Hebrew name for a character, be sure it is actually in Hebrew. the Hebrew language has two sounds not in English, the /ch/ sound and tz sound, and also does not have sounds found in English, specifically the letters J and W. Anglicized versions of names will change a Y to a J and a V to a W or B. Don’t use the anglicized versions of names! Joseph, Jacob, Jonathan, and Joshua are not Hebrew, but Yosef, Yaakov, Yonatan and Yehoshua are Hebrew.

Non-Hebrew names for Jewish Characters

First names

A Jewish character’s secular first name can be almost anything. Take into account your Jewish character’s current country and the countries their family has come from. A woman character with Romanian ties might be named Nadia. A man character in America might be named Jordan. Russian woman might be named Natasha. A non-binary character might name themselves Aspen.

Jewish parents often gave names to their children to help them blend in to avoid discrimination and/or murder. For example, I believe it was either my grandpa or his brother was spared death in Romania because their nickname was a common Romanian non-Jewish name, so they got away from an incident unscathed. Being called Jack instead of Yaakov (the Hebrew version of Jacob) or Joe instead of Yossi or Yosef (Hebrew nickname for and version of Joseph) can literally be the difference between life and death in real life or a story.

Now, do take care not to name a Jewish character something blatantly non-Jewish unless there’s a very good narrative reason. Don’t name them Christian, Christine, Paul, or Mary. Not that it’s impossible for a Jew to be named something like Mary or Paul, but it would be unusual and from a very secular family that gave no shits or didn’t think about the implications and just liked the name. For example, I have known a Jewish woman named Chris (which is a shortened version of the names Christian or Christine). But that’s the real world. When naming a character, you don’t get the luxury of “Oh, I hadn’t thought of that, I just liked the way it sounded.” You need to name characters with intent. Giving a Jewish character in your story a Christian or other religion’s name makes it look like you don’t know what you’re doing. It makes you look ignorant at best, or intentionally white-washing at worst.

Now, a note for some Mizrahi and Sephardi names. Many Arab countries have restrictions on what you are legally allowed to name a child. It was also historically and continues to be extremely dangerous to be Jewish in most Muslim countries. So, Jews who lived in those countries may have Arabic versions of Jewish names. For example, Ibrahim or Maryam instead of Abraham and Miriam. They may also have straight up Arabic names such as Sultana, Suliman, and Amir, and may give these names to their kids even when no longer in a Muslim country simply because they like the name. However, they likely will not be named Muhammad anymore than they would be named Christian or Jèsus.

One quick last thing – Alexander and variants (Alex, Alexis, Alexa, etc) are really popular names, as the Jewish community in antiquity considered Alexander of Macedonia to be a really awesome dude and promised to name their kids after him.

Last names

Traditionally, way back when, Jews used patronyms similar to current Icelandic naming conventions. A person’s last name was Ben or Bat [Father’s Name]. Ben or bat, in Hebrew, translates to son or daughter (with son of being implied). However, gradually around the world, governments began mandating Jews register last names and they were assigned them or chose them. Many Jewish last names imply either a location or a profession. For example, Al-Fassi may be a Mizrahi last name meaning from Fez, Morocco. Cantor indicates a family history of being the one who read from the Torah for the community and led singing of prayers (different from a Rabbi). Rabin means a rabbi, or spiritual leader of the community. Last names ending in -stein, -berg, and -ski are common in Ashkenazi families indicating someone who lived on stony ground in a German speaking land (stein), someone who lived near a mountain in a German speaking land (berg/burg), and someone from a Polish or Slavic speaking land (ski/sky, meaning “from”). Also common are -man and -vitch, and maybe some more I’m forgetting. Ashkenazi families didn’t start using set family last names until around the seventeen to eighteen hundreds, so these names are not

particularly old.

Sephardic Jews didn’t start using permanent last names until around the tenth century or so, and it wasn’t mandated that they were required to adopt permanent last names until the Alhambra Decree of 1492 in Spain, which also expelled the Sephardic Jews from Spain. Sephardic may have Spanish sounding last names either more distinctively Jewish such as Hassan or Sedaka, or as an attempt to disguise Jewish heritage or referring to a location, such as Navarro or Sevilla.

I couldn’t find a lot of information on the historic use of last names for Mizrahi Jews, except to say that it was fairly common early on for them to use last names? But I also saw some contradictory information that said they were more likely to use the patronym system? I’m not an expert. Regardless, Mizrahi last names may vary from location to location, but are often either Arabic influenced names such as Salim, or Judaic names, like Abraham. Sometimes they can indicate a profession, such as the Yemeni Jewish last name Naggar (a carpenter).

There are some special last names that are references to the unique position of a family in Jewish religious life. Here, we need to get into Jewish tribes.

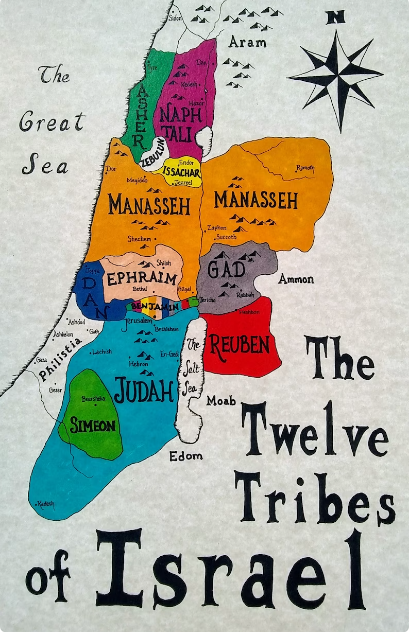

Tribes

To start the explanation, there were originally twelve tribes, said to be named for the children of Jacob, who was renamed Israel. As such, you get the twelve tribes of Israel. However, one of the sons, Joseph, didn’t get one tribe. Instead, he had two sons and they each got a tribe name, Ephraim and Menashe, due to favoritism. The other tribes are Reuven, Shimon, Levi, Yehudah, Issachar, Zevulun, Dan, Naftali, Gad, Asher, and Benyamin [I used the Hebrew phonetic versions of the names instead of anglicized versions]. Now, if you’ve been counting and noticed that if Joseph was one of the twelve sons of Israel and got two tribes, then there should be thirteen! Well, there are, kinda. My understanding growing up was that there’s two reasons its counted as twelve. One is counting Joseph’s tribes of Ephraim and Menashe as one, despite the split into two. The other is that the tribe of Levi got a special purpose separate from the rest of the tribes, instead of getting land. So, while there were technically thirteen tribes, only twelve had designated territory. The tribe of Levi instead had the honor of assisting the kohenim (priests) in the temple, as a reward for not participating in the golden calf situation in the story in the Torah.

A note: all these names can be used for either a (male) first name, or for last names of Jewish characters. I’ve known several people with the last names Asher, Levi, Menashe, and Benjamin.

After the majority of Jews were expelled from their homeland and dispersed into diaspora populations, the knowledge of who came from which tribe was lost. Gad or Naftali didn’t matter, but since all the tribes are said to be descendants of the man named Israel, everyone became part of the singular tribe of Israel/Yisrael.

Well, almost everyone. Here’s where we get to the special names I was talking about. See, in modern times, there’s three Jewish tribes you can be born into. Kohen, Levi, or Israel. Those who are Kohens (also spelled Cohens) are descendants of the priests from ancient Israel, who are said to be the descendants of Moses’s brother, Aharon. They’re a Big Deal, religiously. Those who are Levi are also a big deal, though not as big of a deal. To be part of the Kohenim or the Levi’im you need to be born into the right bloodline from your father’s side. While religion is passed from the mother in Judaism, tribe is passed from the father. Everyone who is not a Kohen or Levi is Israel (also spelled Yisrael). This includes those who have non-Jewish fathers or those who

into Judaism. Since my father is a convert, that makes me part of the tribe of Israel.

There are extra rules, religiously, for Kohens and Levis. For example, a Kohen may not marry a convert or a non- Jew or a divorced person or a widow. They cannot enter a graveyard or place where death has touched and they have specific lines and roles to play in religious ceremonies. Levis also have specific lines and roles to play in religious ceremonies. For example, when reading from the Torah, the first aliyah (going up to read a few lines of the Torah, or say the blessing for it before the cantor reads it) must go to a Kohen. Then the second to a Levi. Then the rest can go to anyone, Israel, Kohen, or Levi. There’s some rules about what to do if one or the other isn’t present, but that’s how things are supposed to go if everything goes right.

With such important roles in religious life, these familial ties are indicated in a lot of names. For example, my maternal grandma is a kohen. We know this because her last name before marriage was Goldman. If a Jew has the name Gold, Goldman, Goldstein, Goldberg, or anything to do with Gold, this is an indication that they are likely from a family of Kohens. It refers not to literal wealth or money, but to having a golden heart and sense of justice. In a way, it’s a code to hide behind an westernized name, while indicating to the Jewish community who they are. Many kohens are named Kohen, Cohen, or Cohn. But Gold is also common, as is Katz. Katz is a name that takes the words “kohen tzadik” meaning righteous kohen and abbreviates it to just the first letters. Like Gold, it’s meant to indicate to other Jews a position of religious importance while not sounding too Jewish to the surrounding Christians who might be prejudice. Of course, in modern times, all these names have become commonly associated with Jews, so the secret code isn’t as useful as it might have once been. Tzadik is also a name that can indicate someone is a kohen, and variations can include Zadik or Zadok. A kohen name from Russia might be Kagan, which is a sort of Russianized version of kohen.

There are also names associated with being a Levi. Levi, Halevi (ha’ meaning the in Hebrew), Levine, Levit, Levitte, Levite, Levinson, Levin, Lewin, Lewinsky, and Loewy are some of the more obvious ones. Then there’s Segan or Segel and variations of that name. Kinda like Katz for a kohen, segan is short for segan lekehunah, or second to the priest. Segal and sgan mean, essentially helper, as in sgan Levi, a helper Levi.

Some Jews when, say, going through Ellis Island, had their names changed either as a deliberate choice or by clerks writing things down wrong. Many Jewish families chose to change their names to less Jewish-sounding names to avoid discrimination. For example, Mr. Rabinowitz couldn’t get a job, but Mr. Robins was hired on the spot.

Decolonization of Names

Some Jews in modern times and through the twentieth to twenty-first centuries are going through a process of de-assimilation and decolonization, reclaiming ancestral language in modern ways by changing familiar surnames forced on their ancestors to Hebrew ones, in addition to using Hebrew first names. Some examples may be taking a name like Jacobowitz and changing it to a Hebrew version, such as Yaakovi. It could mean using the name of a mother or father, or an ancestor worthy of honor, as name like Ben-Gurion. It could mean using the name of a biblical character as a last name, such as David. Place names are also an option, such as Eilat, or words with meanings such as Mazal meaning luck or Shalom meaning peace. Sometimes names will be changed to something that simply sounds similar, such as a name ending in -burg/borg/berg being changed to Barak, meaning lightning. This is less common in diaspora communities, but not unheard of.

As a response to this movement of encouraging changes to create a more monolithic Hebrew identity, some Jews have more recently reverted back to their family’s assimilated names (Germanic, Slavic, Arabic, Russian names, and others) as a statement to preserve the beautiful variety found in many distinctive Jewish ethnic identities rather than a pan-Hebrew identity.

Conclusion

Your character’s last name will say a lot about their heritage and where they come from. It can convey to other Jews, both characters in your stories and potential readers in your audience, what a character’s tribe is, who their family is, and what Jewish ethnicity they are. It also provides lots of opportunity for you as an author to tell us about your character before they’ve even spoken a word, conveying personality, desires, and even potential plotlines. It’s important to get it right so you don’t convey the wrong information.

Below, I’m placing a list of a handful of Hebrew names. This isn’t a comprehensive list, just some I like, that you’re welcome to use for your characters!

10 Hebrew First Names, Unisex

- Aviv – Spring

- Daniel/le – God is my judge

- Gal – wave

- Liron – my song

- Or – light

- Noam – pleasantness

- Rimon – pomegranate

- Sivan – the name of one of the months

- Shir – song

- Tal – dew

10 Hebrew First Names, Girls

- Adina – delicate, mother of Leah and Rachel

- Devorah – A bee, also a prophetess

- Idit – variation of Yudit/Judith

- Leah – delicate, one of the biblical matriarchs

- Malka – queen

- Pnina – pearl

- Rivka – she who ties, biblical character

- Tamara – date palm tree

- Tikva – hope

- Tova – good (female)

10 Hebrew Boy Names

- Adam – Earth/first man, biblical character

- Baruch – blessing

- Dov – bear

- Ezra – help/helper, biblical prophet

- Gershom – stranger, biblical character

- Mordechai – Queen Esther’s uncle

- Moshe – Biblical character, savior

- Natan – given

- Uri – my light

- Yonatan – god gave a gift

If you enjoyed this post, give a like and follow for more content, and leave a comment with your thoughts. Be sure to check me out on Twitter at @EternalEvelyn, YouTube, or Facebook and check out information on my adult paranormal romance novel series, The Bloodline Chronicles!

Linktree assorted social media available here.